Business Judgment Rule in Maryland

The Appellate Court of Maryland recently issued an unpublished opinion in the case of Special Situations Fund III QP, L.P. v. Travel Ctrs. of Am. Inc.[1], in which it analyzed the application of the Business Judgement Rule when a corporate merger is challenged. Unlike in Delaware, where the Business Judgment Rule and the duties of corporate directors have been developed solely by judge-made case law, the Business Judgment Rule in Maryland has been codified by the Legislature at Md. Corps. & Assoc. Code § 2-405.1.[2]

Directors of Maryland corporations are required to act:

(1) In good faith;

(2) In a manner the director reasonably believes to be in the best interests of the corporation; and

(3) With the care that an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would use under similar circumstances.[3]

An act by a director relating to or affecting the acquisition or a potential acquisition of control of the corporation, or any other transaction or potential transaction involving the corporation, may not be held to any higher duty or greater scrutiny than is applied through the statutory Business Judgment Rule.[4]

A director acting in accordance with the standard of conduct set forth in § 2-405.1 has immunity from liability arising from the performance of the director’s duties.[5] The statute also creates a presumption that a director acted in accordance with the Business Judgment Rule.[6]

When a party brings a lawsuit to challenge actions of a board of directors that fall within the board’s business judgment, the claimant must plead specific facts in the complaint sufficient to overcome the Business Judgment Rule.[7] This can be accomplished in either of two ways:

(1) by pleading facts showing fraud or bad faith,[8] or

(2) by pleading facts showing that a director has a conflict of interest relating to the board’s decision, i.e., that the director, or someone close to the director, has a personal financial interest in the outcome of the board’s decision.[9]

If a plaintiff pursues the second route and pleads facts sufficient to show a financial conflict of interest, then the burden will shift to the board of directors to show that its action was just and proper, and that no advantage was taken of the stockholders.[10] In other words, when pursuing the second path, a claimant must plead facts that demonstrate fraud, bad faith, unconscionable conduct, or a conflict of interest – but this can be overcome by the board by showing that the directors with an interest in a contemplated transaction disclosed their conflicts beforehand, or demonstrate that the transactions implicated by those conflicts are fair and reasonable to the corporation.[11] If the board or the stockholders were properly informed of a conflict of interest beforehand, then the contract or transaction may still be authorized, approved, or ratified by a majority of the disinterested board members or stockholders.[12]

[1] 2025 Md. App. LEXIS 1006 (Nov. 25, 2025).

[2] Special Situations Fund, p. 40, n. 3; Hanks, James J., Maryland Corporation Law, § 6.09 6-78 (2d ed. 2020, Supp. 2024).

[3] Md. Corps. & Assoc. Code § 2-405.1(c).

[4] Id., § 2-405.1(h).

[5] Special Situations Fund, p. 41.

[6] Id.

[7] Id., p. 42.

[8] Cherington Condominium v. Kenney, 254 Md. App. 261, 279 (2022); Special Situations Fund, p. 42.

[9] Kenney, 254 Md. App. at 279; Special Situations Fund, p. 43.

[10] Kenney, 254 Md. App. at 279-80; Special Situations Fund, p. 43.

[11] Kenney, 254 Md. App. at 285; Special Situations Fund, p. 61.

[12] Kenney, 254 Md. App. at 283; Sullivan v. Easco Corp., 656 F. Supp. 531, 535 (D. Md. 1987); Special Situations Fund, p. 61.

Maryland shareholder derivative actions must be preceded by a demand on corporate directors to bring suit

Maryland’s intermediate appellate court handed down a decision on August 28, 2025, emphasizing that, in almost all circumstances, a plaintiff must make a demand on corporate directors before initiating a corporate derivative action.[1] A principle known as the “business judgment rule” holds that shareholders in a Maryland corporation ordinarily may not use the courts to override business decisions made by corporate directors.[2] This principle is codified at § 2-405.1 of the Maryland Corporations and Associations Code.

There is, however, an “extraordinary equitable device” through which Maryland shareholders, in limited circumstances, may enforce a corporate right if the corporation itself has failed to assert its rights on its own behalf.[3] This may be accomplished through a “corporate derivative action,” which is essentially a suit by one or more shareholders of a corporation to compel the corporation to sue to protect its own rights, while at the same time also being a suit by the corporation against one or more defendants that are harming the corporation.[4]

Because a corporate derivative suit intrudes on the board of directors’ managerial control of the corporation, a shareholder bringing such a suit is required first to make a demand that the board of directors take action before initiating a shareholder derivative suit.[5] The purpose of requiring this pre-suit demand is to afford the directors of the corporation an opportunity to exercise their reasonable business judgment to decide whether the corporation itself should bring suit.[6]

Required Internal Investigation

Once shareholders make a demand on the corporation, the corporation’s board of directors is required to conduct an investigation into the allegations in the demand and determine whether pursuing the demanded litigation is in the best interests of the corporation.[7] Often, the board will appoint a special litigation committee of independent directors to decide whether the corporation should pursue the litigation.[8] If the board refuses the demand, the complaining shareholder may then bring a lawsuit (commonly referred to as a “demand refused” derivative action).[9] A corporate board’s decision to deny a request to bring litigation would benefit from the same “business judgment rule” presumption as any other decision of the board.[10] In order to establish the right to proceed with a derivative action, the shareholder must overcome a presumption that the board’s decision not to proceed with litigation was the product of proper business judgment.[11]

Demand Excused Derivative Actions

In narrow circumstances, courts have allowed shareholders to bring a derivative action without first making a demand on the board of directors. These are called “demand excused” derivative actions.[12] This type of derivative action – which requires showing that making a prior demand on the board of directors would have been a futile exercise – was analyzed by the Supreme Court of Maryland in its 2001 decision in Werbowsky v. Collomb.[13]

In that case, the court established a narrow standard for allowing “demand excused” derivative actions, holding that the requirement for a prior demand should not be excused simply because a majority of the directors approved or participated in some way in the challenged transaction or board decision, or on the basis of generalized or speculative allegations of director conflicts.[14]

The court concluded that, although “demand excused” derivative actions were not entirely foreclosed, they are strictly limited to situations in which either a demand (or awaiting response to a demand) would cause irreparable harm to the corporation, or a majority of the directors are so personally and directly conflicted or committed to the decision in dispute that they cannot reasonably be expected to respond to a demand in good faith and within the ambit of the business judgment rule.[15]

In short, a demand is required in nearly every derivative action brought in Maryland. The requirement to make a prior demand is not excused simply because the majority of a corporation’s directors approved or participated in some way in the challenged transaction or decision, or on the basis of generalized or speculative allegations that the directors are conflicted or are controlled by other conflicted persons, or would be hostile to bringing a lawsuit.[16]

The Importance of Making a Demand Before Filing a Lawsuit

In its Nathanson decision[17] handed down in August 2025, the Maryland Appellate Court adhered to the Supreme Court of Maryland’s 2001 ruling in Werbowsky, but also addressed a situation in which the party seeking relief attempts to cure an earlier failure to make a demand, by sending a demand after the trial court has dismissed the asserted claims for failing to make a demand. In the Nathanson case, a lawsuit was first brought in federal court by two shareholders against an investment advisory firm and its directors, alleging that the defendants engaged in reckless borrowing practices leading to substantial losses.[18]

The shareholders alleged in their federal lawsuit that applicable Maryland law excused them from making a pre-suit demand on the grounds that making such a demand under the circumstances of the case would be futile.[19] The federal lawsuit was dismissed because a forum selection clause in the firms’ bylaws provided that disputes were to be adjudicated before the Circuit Court for Baltimore City.[20]

Following dismissal of the federal action, the shareholders brought essentially the same suit in the Circuit Court for Baltimore City.[21] On motion, the Circuit Court thereafter dismissed the state court claim, for reasons that included a failure to make pre-suit demand.[22] The shareholders noted an appeal, and a few weeks after the Circuit Court entered its order dismissing the case, the shareholders sent a demand letter to the board.[23]

The board formed a litigation committee, and pursuant to its investigation, notified the shareholders that the committee rejected the litigation demand.[24] The shareholders then brought a new lawsuit in the Circuit Court for Baltimore City, reasserting their derivative claims and asserting that the board wrongfully refused the demand.[25] In their appeal, the defendants argued that, by making the litigation demand after the dismissal of their derivative action, the shareholders rendered their second lawsuit moot.

The court applied the Werbowsky holding and found that the allegations in Nathanson did not satisfy the “very limited exception” to the demand requirement, and did not “clearly demonstrate, in a very particular manner” that “a majority of the directors are so personally and directly conflicted or committed to the decision[s] in dispute that they cannot reasonably be expected to respond to a demand in good faith and within the ambit of the business judgment rule.”[26]

[1] Howard Nathanson, et al, v. Tortoise Capital Advisors, LLC, et al, 2025 Md. App. LEXIS 733 (2025).

[2] Boland v. Boland, 423 Md. 296, 328 (2011); Nathanson, 2025 Md. App. LEXIS 733.

[3] Werbowsky v. Collomb, 262 Md. ___ (599 ( ); Mona v. Mona Elec. Grp., Inc., 176 Md. App. 672, 698 (2007).

[4] Wasserman v. Kay, 197 Md. App. 586, 610 (2011).

[5] Oliveira v. Sugarman, 451 Md. ___, 223 ( ).

[6] Id.; quoting Kamen v. Kemper Fin. Serv., Inc., 500 U.S. 90, 96 (1991).

[7] Shenker v. Laureate Educ., Inc., 411 Md. ___, 344 ( ).

[8] Boland, 423 Md. at 332.

[9] Shenker, 411 Md. at 344; quoting Bender v. Schwartz, 172 Md. App. 648, 666 (2007).

[10] Sugarman, 451 Md. at 223.

[11] Id.

[12] Boland, 423 Md. at 331, n.25.

[13] Werbowsky v. Collomb, 362 Md. 581 (2001)

[14] Id., at 618.

[15] Id., at 620.

[16] Id., at 618.

[17] Howard Nathanson, et al, v. Tortoise Capital Advisors, LLC, et al, 2025 Md. App. LEXIS 733 (2025).

[18] Id., p. (4).

[19] Id., p. (5).

[20] Id., p. (6).

[21] Id., p. (7).

[22] Id., p. (13).

[23] Id., p. (14).

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Nathanson, 2025 Md. App. LEXIS 733, quoting Werbowsky, 362 Md. at 620.

Maryland Tax Changes

The Maryland General Assembly ended its annual legislative session earlier this month. Here is a quick summary of important changes to the state’s tax code:

Increased income taxes for high earners

Beginning in Tax Year 2025, personal income tax rates were increased to 6.25% on income above $500,000, and to 6.5% on income above $1 million. In addition, a 2% tax surcharge will be imposed on capital gains received by taxpayers earning over $350,000 per year. Taxpayers earning above $200,000 per year also will have the value of their personal deductions phase out depending on the level of taxable income above that threshold.

Sales tax on data services and IT services

For transactions on and after July 1, 2025, there will be a 3% sales tax on technology and data services, and related party transactions. Further guidance on the application of this new tax is expected from the Maryland Comptroller during June 2025.

No change to estate tax exemption

A proposed reduction of the Maryland estate tax exemption, from $5 million to $2 million, was not enacted. The Maryland estate tax exemption remains at $5 million.

Increases to government fees and excise taxes

A number of government fees will increase, effective July 1, 2025, including: The vehicle emissions inspection fee will increase from $14 to $30; The cannabis sales tax will increase from 9% to 12%; The vehicle excise tax will increase from 6% to 6.5%; The sports betting tax will increase from 15% to 20%.

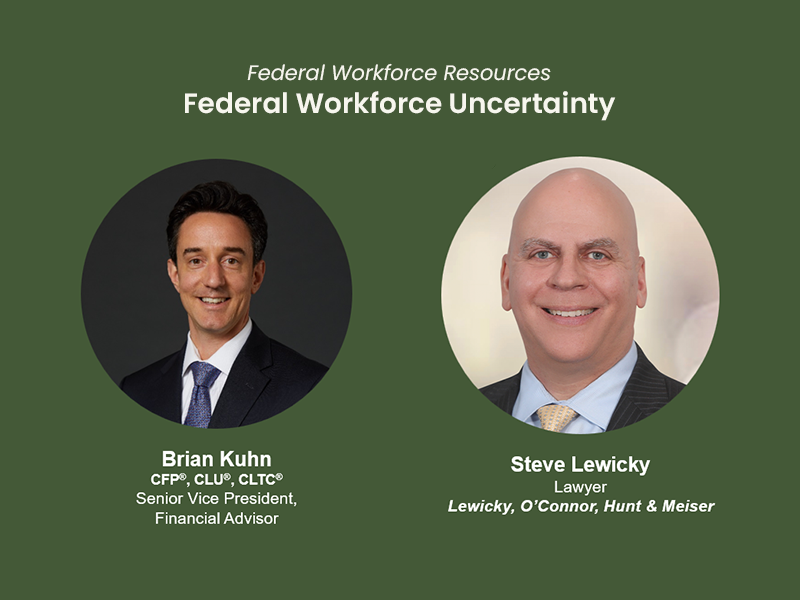

Federal Employment Law: Key Takeaways from Attorney Steve Lewicky

In this recent interview, attorney Steve Lewicky joins Brian Kuhn, Certified Financial Planner at Wealth Enhancement Group, to discuss the latest developments in federal employment law. From court rulings that impact thousands of probationary federal employees to the implications for government contractors facing early termination, this conversation is packed with insights for federal workers navigating uncertain times. Watch the full video below and read on for a detailed summary of the key takeaways.

Watch the full interview on YouTube

Federal Employment Law: Key Takeaways from Attorney Steve Lewicky

About the Speaker

Steve Lewicky is an attorney in Maryland focusing on business law, litigation, and federal employment matters. His firm, located in Howard County, Maryland, regularly advises government employees and contractors on their legal rights.

What’s Happening Right Now in Federal Employment Law?

According to Lewicky, his firm is fielding an influx of calls from both current and former government employees, as well as federal contractors, in light of recent developments. Two major federal court cases—one in Maryland and another in the Northern District of California—have resulted in temporary restraining orders preventing the mass termination of probationary federal employees.

The Maryland Case: A Turning Point

The Maryland recently ruled that the government cannot terminate large numbers of probationary employees without due process—specifically, without providing a performance-related reason or advance notice. Thousands of employees have received notices placing them on administrative leave or informing them of termination, but the court issued an emergency injunction due to the procedures that were employed.

The court ordered that employees be reinstated immediately, and the government was required to submit a written status report confirming compliance.

Can the Government Still Lay Off Federal Employees?

Yes, but only if proper procedures are followed.

Unlike private-sector employment—which is generally “at-will”—federal employment involves more protections. Government employees cannot be terminated arbitrarily, and different rules apply depending on whether someone is a probationary employee or not.

- Probationary Employees: Limited appeal rights. The probationary period may last 1–2 years and can apply to new positions even if the person has served in government for years.

- Non-Probationary Employees: Protected by the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), which allows them to appeal terminations, request reinstatement, back pay, and in some cases, attorney’s fees.

Lewicky emphasized that even probationary employees have some appeal rights, and recent rulings show that courts are scrutinizing how terminations are being handled.

Reduction in Force (RIF): Another Legal Consideration

The government may conduct a reduction in force for budgetary or organizational reasons, but there are also strict rules:

- Advance notice must be given.

- Affected employees must be informed of job placement options.

- In some cases, states must be notified to offer support to displaced workers.

Again, Lewicky stressed that while RIFs are legal, failing to follow the proper process can make the actions unlawful.

What About Federal Contractors and Subcontractors?

Federal contractors are also facing increased uncertainty. While every contract is different, most contain a “termination for convenience” clause allowing the government to end the contract at any time—even if performance has been adequate.

However, when this happens:

- Contractors must cease work immediately.

- Contractors must document all costs associated with the wind-down.

- The government must compensate for incurred costs and unpaid work completed.

Lewicky noted that contractors should seek legal counsel immediately upon receiving a termination notice due to the complex and strict timeline involved in appealing or negotiating a fair settlement.

Legal Support and Consultations

Steve Lewicky’s firm offers initial consultations, either via Zoom or in person, to help federal employees and contractors understand their rights and options. They’re currently speaking with a high volume of individuals affected by these changes and are available to assist with legal strategy and appeals.

Conclusion

If you’re a federal employee or government contractor navigating recent changes, it’s more important than ever to understand your rights and the proper legal procedures. These recent court rulings show that the government must follow specific rules, even in times of large-scale employment changes. Whether you’re facing termination, administrative leave, or contract wind-down, speaking with an experienced federal employment attorney can help protect your interests.

Trump Administration Seeks to Void Union Contracts for a Large Portion of the Federal Workforce

On Thursday, March 27, 2025, President Trump issued an executive order seeking to end union representation for a large portion of the federal workforce. Later that day, eight federal agencies brought suit against unions representing a large swath of federal employees, seeking a court order declaring all existing union contracts between those unions and the plaintiff government agencies to be void, in light of the executive order.

In this lawsuit (U.S. Dept. of Defense, et al, v. American Federation of Government Employees, AFL-CIO, District 10, et al, W. Dist. Tex., Case No. 6:25-cv-00119), the Government asserts that a top priority of the Trump Administration since taking office has been “to improve the efficiency and efficacy of the federal workforce, and to promote the national security of the United States,” and goes on to allege that “[u]nfortunately…departments and agencies have been hamstrung…by restrictive terms of collective bargaining agreements” with government employee unions.” The government then argues that “inflexible [collective bargaining agreements] obstruct presidential and agency head capacity to ensure accountability and improve performance.”

Government employees at some core national security agencies, such as the FBI, CIA, NSA and U.S. Secret Service, have always been excluded from the right to unionize that was granted by Congress in the Federal Service Labor-Management Relations Act in 1978. Since the late 1970s, however, federal employees outside of those few exempted agencies have had the right to join unions and to engage in collective bargaining (though not the right to strike or to bargain over pay levels). Congress included in the 1978 statue flexibility for a future president to exclude employees of agencies beyond the FBI, CIA, NSA and Secret Service from the right to collectively bargain through unions, but only if the president makes a determination that an agency or department outside of the FBI, CIA, NSA or Secret Service has, as one of its “primary functions,” intelligence, counterintelligence, investigative or national security work that would be incompatible with permitting collective bargaining by its workforce. The statute does not define the terms “national security work” or “investigative work.”

In the new lawsuit, the Administration seeks to take away union and collective bargaining rights from employees at a broad range of agencies, including not only the Defense Department and the Department of Homeland Security, but also the Departments of Agriculture, Housing and Urban Development, Justice, Veterans Affairs and the EPA and Social Security Administration. Notably, none of President Trump’s predecessors since the late 1970s have made such a finding for these other agencies, nor did President Trump do so during his first term.

The new executive order excludes police and firefighter unions from its scope, even though these functions would seem to fit within activities associated with national security. Commentators have noted that these law enforcement unions were the only federal employee unions that endorsed the candidacy of President Trump during the 2024 election campaign.

The Government filed its lawsuit in the Western District of Texas, Waco Division, which is one of the handful of federal courthouses across the country that has only a single judge — a Trump appointee. In Federal District Courts with more than a single judge, judges are assigned to new cases based on random blind assignment to protect against “court-shopping” by plaintiffs. In single-judge Federal courthouses, there is no uncertainty about which judge will be assigned to a newly filed case, since there is only a single judge to assign.

The combined acts of declaring a large portion of the federal workforce to be ineligible for union representation, and then seeking a court order to void all contracts between those employees’ unions and the Government, carry a strong odor of union-busting. Government employee unions have been at the forefront of bringing lawsuits during the first months of the Trump Administration to challenge the legality of a large number of Administration actions. Elections have consequences, however, and one of these is to place in power a new Administration that can exercise discretion granted by Congress in previously enacted statutes. It will be interesting to see what level of review and scrutiny the federal court in Texas (and appellate courts) give to this executive order, and specifically the President’s determination that some agencies with core functions that seem to be outside the national security space are, in fact, performing national security work or investigative work.

Courts order reinstatement of federal employees, but the Administration moves forward with future reduction in force plans

It’s a stressful and confusing time for federal employees. In recent days, two U.S. District Court judges – one in Maryland and the other in California – issued sweeping nationwide injunctions compelling the Government to pause employee terminations and to reinstate a large number of recently terminated federal employees. In both cases, the courts found that recent terminations of probationary employees were unlawful because they were undertaken by the Office of Personnel Management (#OPM) (the government’s human resources office) and not by the federal agencies where the employees actually worked, and because the Government did not adhere to notice and timing requirements.

In the Maryland case, Maryland v. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, et al, U.S. Dist. Ct. Md., Case No. 1:25-cv-00748, Judge James Bredar entered a Temporary Restraining Order (#TRO) on March 13, 2025, ordering the covered cabinet agencies to reinstate all employees, throughout the United States, who were previously employed by the covered agencies and were “purportedly terminated” by the Government on or after January 20, 2025. Eighteen U.S. Government agencies and departments are covered by this TRO. The covered agencies were also ordered to undertake no further reductions in force (#RIFs), “whether formally labeled as such or not,” except in compliance with notice requirements established by federal statute and regulations. In order ensure compliance by the Government, Judge Bredar ordered the government agencies and departments to submit a detailed status report to the court by mid-day next Monday, March 17, setting forth the number of employees reinstated by the Government, broken down by agency. The court also scheduled a hearing for March 26, to determine whether a longer-duration preliminary injunction will be entered. The TRO does not prohibit the Government “from conducting lawful terminations of probationary federal employees – whether pursuant to a proper RIF or else for cause, on the basis of good-faith, individualized determinations,” but may not do so “as part of a mass termination.”

In a 56 page memorandum opinion accompanying the TRO, Judge Bredar noted that, under Title 5 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), civil service employees are considered to be under probationary status during the first year or two of their employment, and a probationary employee may lawfully be terminated if his or her work performance or conduct fails to demonstrate fitness or qualification for continued employment, or for reasons based on conditions arising prior to his or her employment. If the Government decides to terminate a probationary employee, however, Title 5 of the CFR requires the Government to notify the employee in writing as to why the decision to terminate was made, including a statement of the agency’s conclusions as to the inadequacies of the employee’s performance or conduct. The only other way properly to terminate a probationary civil service employee is as part of a reduction in force (RIF) – but federal statutes and regulations establish detailed procedures that must be followed by federal agencies when conducting a RIF. The Title 5 regulations include a requirement that, when conducting a RIF, an agency follow certain retention preferences that are set forth in Title 5 of the U.S. Code, which create priorities such as by length of service, military service preferences, and performance ratings. The regulations also require, in a RIF, that the agency establish “competitive areas” in which employees compete for retention, and rank employees for intention based on the retention factors discussed above. In most circumstances, an agency conducting a RIF must provide employees at least sixty days written notice before termination, and even in extraordinary circumstances must provide thirty days prior written notice. For larger scale RIFs, notice also must be provided to affected states, so that state governments have an opportunity to carry out “rapid response activities” to assist dislocated employees in obtaining new employment.

Judge Bredar noted that, on February 11 and 12, various agencies of the U.S. Government terminated large numbers of probationary employees, with further terminations occurring in the weeks thereafter. The court determined that these terminations were not based upon qualifications or performance, noting that the termination notices did not even cursorily identify any issues with the individual’s performance, but instead explained that the termination was “in the public interest” or “due to the priorities of the current administration.” The court found that the Government’s actions reflected that these terminations were in fact RIFs – but did not adhere to statutory RIF requirements.

The TRO issued by Maryland federal court was broadly consistent with a TRO entered at almost the same time by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, which ordered the Government to pause firings and to reinstate probationary employees at six government agencies. Earlier, on March 5, a similar decision was handed down by the Merit Systems Protection Board (#MSPB), ordering reinstatement of probationary employees that were terminated at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

As of the time of this post, it appears that at least some agencies are moving forward with reinstatement and payment of back pay in response to the court orders, but it is not clear if all covered agencies are doing so. More clarity should be forthcoming on Monday, March 17.

The two TROs are being appealed by the Government, and issuance of a TRO does not necessarily mean that the same relief will be granted by the court later at the preliminary injunction stage, or after a trial on the merits. Beyond the possibility that these TROs may be overturned on appeal or modified by the issuing courts at the preliminary injunction stage, it’s also important to recognize that the legal reasoning set forth in these two emergency orders does not preclude the Government from reducing the size of the federal workforce using the RIF procedures set forth in federal law. The Government just needs to follow the rules, procedures and timetables that are mandatory in RIFs. News outlets have reported in recent days that agencies have already been given guidance by OPM to plan for RIFs, so presumably the agencies and OPM intend to pursue RIFs down the road even if the firings of probationary employees during late February and early March are reversed due to the Government’s failure to comply with RIF requirements when taking those actions.

Government Employees Receiving Notices of Termination: Now What?

Our firm has been contacted in recent days by many US Government employees that have received letters informing them that their employment will be terminated “for cause” in thirty days. Most of these have been accompanied by separate letters putting the employee on administrative leave for the intervening thirty days. Situations vary by agency, by status of the employee, and by other factors, but in all cases it’s important for these employees to understand their rights.

US Government employment is not “at will” – the type of employment relationship that is common in the private sector. Termination of government employment is subject to and controlled by federal statutes that establish Civil Service employment protections. If a federal employee is terminated or disciplined without cause or reason, those employment actions may be appealed to the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), an independent agency of the government. The Merit Systems Protection Board hears appeals when the government takes adverse employment actions like removals and terminations, suspensions of more than 14 days in length, reductions in pay or grade, or performance-based employment actions. It can award remedies that include back pay accruing after the date of termination, reinstatement in the position, and sometimes reimbursement of attorneys’ fees.

An employee’s appeal rights are greatly affected by whether they are still in a probationary period. The government can remove a probationary employee subject only to limited rights of appeal. Outside of probationary periods, government employees have broad rights of appeal from a termination or removal decision.

While some agencies appear to be terminating large numbers of employees at the same time by alleging “cause” for removal, some agencies may also try to reduce head count using established workforce reduction programs, such as: (a) voluntary separation incentive payments (VSIPs), (b) voluntary early retirement authority (VERA), or involuntary separations by a reduction in force (RIF). Agencies also appear, in some cases, to be attempting to reduce their workforce by reassigning employees to a different office location, often at great distance, and then terminating employment if the employee refuses to relocate.

Federal employees receiving an offer of voluntary separation incentive payments (VSIPs) and/or an offer of voluntary early retirement (VERA) should closely examine the proposed terms of these offers, and will benefit from having legal counsel review any such proposals. Reductions in force (RIFs) can only be undertaken in conformance with government regulations on RIFs, and the government should be held to these requirements.

Lewicky, O’Connor, Hunt & Meiser helps current and former US Government employees navigate the current upheavals in federal employment. Every person’s situation is different, but in most cases it is very important for a government employee receiving notice of termination or of other adverse employment action to promptly provide a written objection response to the agency, and to file an appeal to the Merit Systems Protection Board within the fixed time period for doing so. We guide our clients in taking these steps. Equally important, recent government actions and pronouncements suggest that the government may be contemplating employment actions that are not in compliance with applicable laws. This makes it even more important to have legal counsel to analyze and explain new or unprecedented developments, as the occur.

You received a stop-work order from the Government – What do you do next?

The Trump Administration, during its first weeks in office, has suspended or terminated a large number of federal contracts, and an even larger number of contracts may now be at risk of suspension or termination. The General Services Administration (GSA) also has been taking steps to terminate leases for government offices and facilities. Government contractors need to understand their rights in this challenging environment.

Procurement contracts are subject to the Federal Acquisition Regulations (the “FAR”), and almost always include standard FAR clauses that allow the Government to terminate or freeze the contract for the Government’s own convenience, without any default by the contractor.

A stop-work order is a written order from the contracting officer that requires a contractor to stop all or part of the work on a government contract for ninety days (or longer, if the parties agree to an extension). A contractor receiving a stop-work order has to immediately comply with the terms of the order, and take reasonable steps to mitigate costs related to the work covered by the order. If the stop-work order is not canceled within ninety days, the contracting officer will either cancel the stop work order or terminate the contract. After the stop-work order is cancelled or expires, the contractor then has thirty days to request an equitable adjustment or submit a claim for payment for costs incurred based on the stop-work order. If the contract is terminated, the contractor is entitled to reasonable costs in any termination settlement agreement.

A contracting officer also may suspend work and freeze a contractor’s performance on a procurement contract. Suspensions of work can suspend, delay, or interrupt all or part of the work for a period of time that is determined by the contracting officer. A suspension of work order may be in writing, but does not have to be. If a contracting officer constructively suspends work without a written suspension order, it is important for the contractor to memorialize the suspension in writing to the Government within a short period following the onset of the suspension.

When terminating a contract for its convenience, the Government has to provide written notice to the contractor that the termination is for convenience, and the notice must state the effective date of the termination. Although the Government cannot act in bad faith in making a decision to terminate a contract for convenience, it is a very high burden for the contractor to overcome a legal presumption that the Government took its action in good faith.

Even if the contractor does not allege bad faith by the Government in exercising its right to termination, the contractor still has a right to receive fair compensation for work performed and for preparations made for the terminated portions of the contract, including a reasonable allowance for profit. To pursue a remedy, the contractor must submit a “termination settlement proposal” within one year of the effective date of termination – unless an extension is granted by the contracting officer. The parties will then try to negotiate the terms of a termination settlement, which may include reasonable profit for work that has been completed. Contracting officers have discretion to take fairness considerations into account in settlement negotiations, but a termination settlement agreement must adhere to cost principles and procedures set forth in FAR Part 31. If the parties are unable to reach agreement, then the contracting officer will issue a final decision, which can be appealed to the agency’s contract review board or to the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.

The Contract Disputes Act establishes the process by which contract disputes are resolved with the Government. Under this law, a contractor must submit a claim, in writing, to the contracting officer within six (6) years after accrual of the claim. The written claim must demand payment of a sum certain – which in some circumstances is a surprisingly difficult exercise. Claims exceeding $100,000 must be certified by an individual authorized to bind the contractor. Under most circumstances, the contracting officer has sixty days to issue a final decision on a filed claim — unless the contracting officer notifies the contractor within those sixty days of a different time period for issuing the decision. The contracting officer’s decision can be appealed to the particular agency’s appeal board within ninety days, or to the U.S. Court of Federal Claims within twelve months. If the contracting officer fails to issue a final decision within sixty days (or within such other time period the contracting officer previously established), the claim is considered to be a “deemed denial,” allowing the contractor to appeal the denial.

Separate and distinct from procurement contracts are grants and cooperative agreements by which government agencies make awards to non-governmental entities. These grants and agreements are referred to collectively as “federal financial assistance,” and are governed by Subparts A through F of 2 C.F.R. § 200. “Grants’ do not anticipate substantial involvement of a Government agency to carry out the activity in the agreement, while “cooperative agreements” have agency involvement.

Government grant officers can only terminate a federal financial assistance award for convenience if the terms and conditions of the award permit termination for convenience, and if the “award no longer effectuates the program goals or agency priorities.” Costs associated with a termination or suspension are only allowable if the federal executive agency expressly authorizes them in the notice of termination or notice of suspension. However, suspension costs or post-termination costs are allowable if the arise from financial obligations which were properly incurred by the recipient or subrecipient before the effective date of suspension or termination, and not in anticipation of it; and if the costs would be allowable if the award was not suspended or expired normally at the end of the period of performance in which the termination takes effect. Recipients are typically entitled to termination settlement costs that the recipient is unable to discontinue after the termination date. Each agency has its own process for making objection to terminations of a financial assistance award, and for hearings and appeals

If faced with an actual or anticipated government contract termination, federal contractors need to take these steps:

• Fully understand the contract terms. It is important to understand the type of contract involved, and the contract’s exact terms. This provides the groundwork for how to dispute the Government’s action, or any delay in payment.

• Document termination costs. It’s also very important to obtain and maintain detailed documentation of all costs arising from a contract termination, suspension, or stop-work order – or from delays in payment. A government contractor is going to have to demonstrate to the contracting officer all costs arising from the Government’s action.

• Give clear written notice to the contracting officer. A contractor hit with an adverse action should immediately notify the contracting officer, in writing, that the government contractor believes a stop-work order or suspension of work has given rise to costs, and that the contractor intends to seek and award of those costs in the form of a contract claim, once the suspension ends, the stop-work order is lifted, or the Government formally terminates the contract.

• Follow all required procedures when filing a claim or appeal, and meet all deadlines. The relevant claim submission process and/or appeals process has to be complied with rigorously, including all filing deadlines. Typically, a claim for a stop-work order must be submitted within thirty days of cancelation or expiration of the order.

Tax Considerations When Buying or Selling a Business in Maryland

When structuring the purchase or sale of a business in Maryland, one of the most important tax considerations is a choice between structuring the transaction as a stock sale or an asset sale. This decision has been covered at greater length in another article that I recently authored, but in very brief summary: A stock sale is typically the structure preferred by sellers, since a seller typically pays the capital gains tax rate on a stock sale, and the buyer retains the existing tax basis in assets. An asset sale is generally preferred by buyers, as asset sales provide a step-up in basis for depreciation purposes. This article will review other tax issues, beyond the “stock sale v. asset sale” question.

Bulk Sales Tax

Maryland applies a 6% tax to tangible personal property that is included in a business sale. The Bulk Sales Tax applies to furniture and fixtures, computer software, business records, customer lists, and non-capitalized goods and supplies. There are exemptions from application of the Maryland Bulk Sales Tax, including the following:

The “Resale Inventory Exemption” exempts from Bulk Sales tax tangible personal property that was purchased for purposes of resale. To benefit from this exemption, a seller must have maintained documentation demonstrating that the subject inventory was held exclusively for resale. The seller also must obtain a resale certificate from the purchaser.

The “Manufacturing Equipment Exemption” exempts from Bulk Sales tax manufacturing equipment and machinery that is used directly in the production process, and that passes a “used directly” test that is established under Maryland state tax regulations.

The “Motor Vehicle and Transportation Equipment Exemption” exempts sales of vehicles and transportation equipment that are required by the State of Maryland to be titled and registered. These are instead subject to excise taxation under the Maryland Transportation Code.

Some types of “Occasional Sales” also are exempt from Bulk Sales taxation, if they are casual and isolated sales that the company does not regularly engage in as part of the business. These must be one-time or isolated transactions that are undertaken no more than three times in any twelve-month period.

The “Affiliated Entity Transfer Exemption” may except from Bulk Sales taxation certain transfers that are between two entities that have common ownership at a level of 80% or greater, as long as the common ownership continues for at least two years after the transfer.

To support any or all of the above exemptions from Bulk Sales taxation, the company must maintain contemporaneous documentation supporting the exemption(s), such as copies of written agreements specifying the exempt assets, as well as resale or exemption certificates where applicable. Failure to properly document exemptions can result in assessment of the tax, with interest and penalties, along with personal liability for responsible parties.

Sales and Use Tax

Maryland has a Sales and Use Tax that may apply to transfers of tangible personal property in the sale of a business. Maryland law provides several potential exemptions from these taxes, which may apply when there is a sale of an entire business.

The sale of an entire business or of a complete business division may qualify for exemption if the sale encompass all or substantially all of the business assets, the assets are sold as a going concern, and the purchaser continues the same type of business operation following the transaction. The following asset classes remain subject to sales and use taxation, however, even if the transaction as a whole is exempt: (1) inventory not held for resale, (2) office equipment and supplies, (3) non-production equipment, and (4) consumable supplies.

The statute also provides an exemption for casual and isolated sales, which may apply to the sale of an entire business when the transaction is properly structured. To benefit from this exemption, the sale transaction may not be of a type that is regularly engaged in by the seller, and it must be infrequent and not part of a series of sales. The seller must not be regularly engaged in the business of selling similar items. No more than three sales may occur within a twelve-month period, and the exemption applies only to sellers not otherwise required to hold a Maryland sales tax license.

Maryland law also provides an exemption for some statutory mergers, consolidations, and other types of qualifying corporate reorganizations. To qualify under this exception, the transaction must qualify as a tax-free reorganization under IRC § 368, must be between qualifying business entities, and proper documentation of the reorganization must be maintained.

Real Property Transfer and Recordation Taxes

If the sale or purchase of a Maryland business includes the transfer of real property, then a county or local Transfer and Recordation Tax will apply, based on the amount of consideration paid for the real property in the transaction. Maryland appellate courts have recently made clear that Transfer and Recordation Taxes are not to be based upon the value of any intangible business assets transferred in the transaction, or on Goodwill, or on the value of transferred business licenses. This makes proper allocation of the purchase price between real and intangible property an important part of any purchase and sale agreement, where real property is a component of the transaction.

Summary

Careful tax planning in Maryland business sales transaction can yield significant savings for both parties. During the due diligence process prior to consummation of a business sale, it is important for the due diligence team to review past tax returns and filings, to ensure compliance with bulk sales requirements, and to assess any transfer tax obligations. It is good practice to model the tax impact of different deal structuring options, and to consider both parties’ tax objectives during negotiations. It’s also important to comply with bulk sales notice and payment requirements, where applicable to a particular transaction. The optimal structure and transaction terms depend on specific circumstances of a particular transaction, and may require balancing competing tax objectives.

None of the information provided in this article constitutes legal advice or tax advice. Every situation is different and should be thoroughly reviewed by and discussed with your legal and tax advisors. Please do not rely on the contents of this article as the basis for making decisions regarding your particular situation. If you are contemplating the purchase or sale of a business in the State of Maryland, Lewicky, O’Connor, Hunt & Meiser stands ready to provide legal support for your contemplated transaction.

Structuring the Purchase or Sale of a Business: Asset Sale vs. Stock Sale

There are three ways to structure the purchase or sale of a business: As a sale of a corporation’s stock or of a limited liability company’s member interests (generically referred to as a “stock sale”), as a sale of some or all of the company’s assets, or through a merger. Each of these approaches offer its own advantages and considerations for Buyers and Sellers, including tax implications, liability exposure, and the relative complexity of the transaction. Liability exposure can be a very important consideration, but in this article I will be discussing only the tax implications of selecting between an asset sale and a stock sale.

Tax Advantages to Buyers in an Asset Sale

Beyond gaining protection from assuming the liabilities of the acquired business, a significant benefit for the Buyer in an asset sale is the ability to step up the tax basis of acquired assets to their fair market value. This can yield substantial and ongoing financial benefit to the Buyer. The stepped-up basis mechanism allows Buyers to reset the tax basis of acquired assets to their purchase price, rather than inheriting the Seller’s existing tax basis. As an example, let’s consider a piece of manufacturing equipment:

In a stock purchase, if the original owner purchased the equipment for $200,000, claimed $150,000 in accumulated depreciation, and the equipment at the time of the acquisition has a fair market value of $120,000, the Buyer would inherit a tax basis of $50,000 ($200,000 – $150,000), would have limited future depreciation deductions, and would have a potential taxable gain of $70,000 if the asset is later sold at its $120,000 fair market value. In an asset purchase, however, the Buyer would receive a new tax basis of $120,000 (the current fair market value), would gain access to fresh depreciation deductions calculated from the stepped-up basis, would minimize or eliminate taxable gain on any future sale at fair market value, and would generate higher annual tax deductions, thereby improving cash flow. Stepped-up basis extends across various asset categories, including physical assets (buildings, equipment, and furnishings), intangible assets (patents, trademarks, and customer relationships), and goodwill.

For corporations in the 21% corporate tax bracket, the tax savings from stepped-up basis can be substantial. If a transaction includes $500,000 in stepped-up basis, the Buyer could realize tax savings of $105,000 over time, through increased depreciation deductions. These tax advantages often influence acquisition negotiations, since Buyers may be willing to pay a premium for assets due to the long-term tax benefits of stepped-up basis. This benefit has to be weighed against the Seller’s potential need for a higher purchase price to offset its increased tax burden in an asset sale.

Another benefit for the Buyer in an asset sale are opportunities for enhanced depreciation and amortization deductions, thanks to the step-up in basis. Depreciation applies to tangible assets such as buildings, equipment, and vehicles, while amortization applies to intangible assets (patents, customer relationships) and goodwill. Both mechanisms allow companies to deduct the cost of assets over their prescribed useful lives, reducing taxable income and generating tax savings. As an example, let’s consider a transaction involving manufacturing equipment valued at $500,000, customer relationships valued at $250,000, and a commercial building valued at $1,000,000. In a stock purchase, the Buyer will inherit the Seller’s existing tax basis. If the Seller has already claimed significant depreciation, the Buyer’s future deductions would then be limited. For instance, if the equipment has a depreciated basis of $100,000, the Buyer could only claim future depreciation on that amount, even though the Buyer presumably paid market value for the equipment in the acquisition transaction. In an asset purchase, however, the Buyer can claim depreciation and amortization based on the full fair market value of the assets. In the above example, the manufacturing equipment (valued at $500,000, with a 7-year depreciation schedule), would have annual depreciation of about $71,428, with an annual tax savings of about $15,000 at a 21% corporate tax rate. That would be a tax savings over the depreciation period of $105,000. The customer relationships (valued at $250,000 in this example, with a 15-year amortization schedule), would result in an annual amortization of $16,667, and annual tax savings (at a 21% corporate rate) of $3,500, for a total tax savings over the amortization period of $52,500. The commercial building (valued at $1,000,000 in this example, with a 39-year depreciation schedule), would have annual depreciation of about $25,641, yielding annual tax savings of $5,285 at a 21% corporate rate, resulting in aggregate tax savings over the depreciation period of $210,000.

The tax code may provide further opportunities to accelerate these benefits through its bonus depreciation provisions. Current tax law allows for 100% first-year bonus depreciation on many qualifying assets, enabling immediate write-off of their entire cost. While this provision doesn’t apply to buildings or to most intangibles, it can significantly accelerate tax benefits for eligible assets.

The parties may state, in their purchase-sale agreement, an agreed upon allocation of the purchase price, which can affect the timing of tax benefits. Buyers often benefit from allocating more of the purchase price to assets with shorter recovery periods. Any agreed-to allocation must be reasonable and supportable, however, in order to pass muster with the IRS.

Enhanced depreciation and amortization can create temporary differences between book and tax income, resulting in deferred tax liabilities. These enhanced deductions represent a significant financial advantage of asset purchases, often justifying higher purchase prices or providing additional negotiating leverage. The present value of accelerated tax savings can materially improve the Buyer’s return on investment and provide additional cash flow for debt service or business reinvestment.

Another significant financial advantage to an asset purchase is the ability to amortize goodwill for tax purposes. This is not available in a stock purchase. Goodwill emerges when a Buyer pays more than the fair market value of identifiable assets, reflecting the additional value attributed to intangible factors such as brand reputation, customer relationships, employee expertise, market position, and potential synergies. This premium often represents a significant portion of the purchase price in business acquisitions. Goodwill can be amortized over a 15-year period, generating substantial tax savings for the acquiring company.

If a Buyer acquires a business for $5 million, but the identifiable assets have a fair market value of $3.5 million. The $1.5 million difference represents goodwill. The tax treatment of this goodwill varies dramatically between asset and stock purchases. In a stock purchase transaction, the Buyer receives no tax benefit from the goodwill premium. While the goodwill is recognized for accounting purposes, it cannot be amortized for tax purposes, resulting in no tax deductions over the life of the asset. In an asset purchase transaction, however, the tax treatment can be far more advantageous. In the above example where there is $1.5 million in goodwill, there would be an annual amortization deduction of $100,000 ($1.5 million over 15 years), which would yield annual tax savings of $21,000 at a 21% corporate tax rate, and total tax savings over 15-year period of $315,000. This tax treatment not only converts what otherwise would be a non-deductible purchase premium into tax-deductible amortization over the amortization period, but also allows companies to forecast tax benefits with certainty. The present value of goodwill amortization tax savings often justifies paying a higher purchase price.

To secure these tax benefits, Buyers must ensure that the allocation to goodwill stated in the purchase-sale agreement is reasonable and supportable, is based on proper valuations, documented in the purchase agreement, and is reported consistently on tax returns. While tax treatment allows for straight-line amortization, accounting rules require periodic impairment testing, which requires separate tracking systems, deferred tax accounting, regular monitoring and reporting, and compliance with tax and accounting requirements.

The goodwill amortization benefit represents one of the most compelling reasons Buyers generally prefer asset purchase structures. The ability to generate substantial tax savings over a 15-year period often influences both deal structure and purchase price negotiations.

Advantages to Sellers in an Asset Sale

Although the asset sale structure generally favors Buyers, Sellers potentially can receive a higher purchase price in an asset sale, to offset tax implications, and an asset sale gives a Seller the ability to retain particular assets or intellectual property. If some but not all of the business assets are sold, then the Seller has the option of continuing to operate with its retained assets (if not prohibited from doing so in the purchase-sale agreement), and the Seller may have some flexibility in handling remaining liabilities of the business.

Tax Advantages to Sellers in a Stock Sale

Stock sales typically provide Sellers in corporate acquisitions with more favorable tax treatment than do asset sales, and Sellers therefore often prefer this transaction structure. Tax advantages come in the form of lower effective tax rates and simplified tax treatment. The fundamental tax benefit of a stock sale lies in its single-level taxation at preferential capital gains rates. When corporate shareholders sell their stock, they pay tax only once, on the difference between the sale price and their basis in the stock. Current federal long-term capital gains rates max out at 20%, but with additional state taxes that vary by state. Let’s take the example of a C-Corporation sale with a sale price of $5 million, and a tax basis of $3 million, resulting in a capital gain of $2 million. With an asset sale, this transaction would result in double taxation. First, the C-Corporation would recognize the $2 million gain that would be taxed at the federal corporate tax rate of 21%, resulting in a corporate tax liability of $420,000, and net proceeds to the corporation after this tax of $4.58 million. Thereafter, if or when the proceeds are distributed to shareholders, the federal capital gains rate of 20% will be applied to this $4.58 million, resulting in shareholder tax liability of $916,000. The combined tax burden at both levels of taxation in this example would be $1.08 million, resulting in an effective tax rate on the gain of about 67%.

The same transaction structured as a stock sale would result in a single level of taxation at the shareholder level. In the above example, the $2 million gain would be taxed at the 20% federal capital gains rate for a total tax liability of $400,000, for an effective tax rate on the gain of 20%. In this example, there would be a tax savings for the Seller of $935,000, comparing the tax sale scenario to the asset sale scenario.

Capital gains rates present a substantial advantage over ordinary income tax rates, of course. While ordinary income tax rates can reach 37% at the federal level, long-term federal capital gains rates are typically 20% for high-income Sellers, with additional state tax rates varying by jurisdiction. To secure capital gains treatment, stock must be held for more than one year to qualify for long-term capital gains rates, the transaction must represent a genuine sale or exchange of a capital asset, the Seller must maintain proper documentation of their basis in the stock, and the sale must be properly structured and executed.

C-Corporations benefit most dramatically from stock sale treatment, as a stock sale eliminates the double taxation inherent in the C-Corporation structure. The avoidance of corporate-level taxation represents a pure tax savings that flows directly to shareholders’ bottom line. The above example considered a C-Corporation, but tax treatment depends on entity type.

S-Corporations also benefit from stock sale treatment, though the advantage is more nuanced. While S-Corporations generally avoid double taxation even in asset sales, stock sale treatment ensures the entire gain receives capital gains treatment, rather than having portions potentially taxed as ordinary income depending on the character of underlying assets.

Limited Liability Companies and partnerships, when selling membership interests or partnership interests, typically receive treatment similar to stock sales, providing comparable tax benefits to their owners — but asset sales for partnerships may result in ordinary income treatment for certain assets, and there may be complexity in allocating gain among partners.

In addition to having advantage in applicable rates of taxation, stock sales also eliminate concerns about depreciation recapture that may occur in asset sales, where equipment and machinery gains may be taxed as ordinary income, real estate depreciation may be recaptured at 25% rates, and other asset classes may trigger different tax rates. Stock sales also eliminate the need to characterize gain on an asset-by-asset basis, thereby reducing complexity in state tax compliance, simplifying tax reporting and compliance, and providing greater certainty in tax outcome. Stock sales also can avoid multiple state tax filing requirements, reduce exposure to state transfer taxes, and simplify compliance across jurisdictions.

Advantages to Buyers in a Stock Sale

While the stock sale structure typically favors Sellers, a stock sale gives the Buyer a simpler transaction structure, with fewer formal requirements, along with automatic transfer of contracts, licenses, and permits. There is no need to retitle individual assets, as there would be in an asset sale. A simpler transaction structure results in reduced transaction costs and complexity. A stock sale also allows seamless continuation of business operations, preserves existing contracts and relationships of the business, maintains existing permits and licenses, and retains the corporate entity and tax attributes.

Section 338(h)(10) Election

In some circumstances, Section 338(h)(10) of the Internal Revenue Code provides a sophisticated mechanism that allows C-Corporations to combine the legal benefits of a stock sale with the tax advantages of an asset sale. This election represents a hybrid approach, where the transaction is legally executed as a stock purchase while being treated as an asset purchase for federal tax purposes. To qualify for this election, the purchasing entity must be a corporation (not an individual or partnership), the Buyer must acquire at least 80% of the target company’s stock in a taxable purchase, the target must be either an S corporation or a subsidiary member of a consolidated group, and both Buyer and Seller must formally agree to make the election.

When a Section 338(h)(10) election is made, the transaction is treated as a hypothetical asset sale followed by a liquidation of the target company. The target company is deemed to have sold all its assets to a new corporation at fair market value, and the Buyer receives a stepped-up tax basis in the acquired assets. For S corporations, shareholders experience a single level of taxation. The transaction avoids double taxation typically associated with C corporation asset sales.

The Buyer obtains stepped-up basis in assets for enhanced depreciation and amortization, benefits from the legal simplicity of a stock acquisition, avoids need to transfer individual assets or obtain third-party consents, and preserves valuable contracts and permits that might be non-transferable. The Seller achieves potentially higher purchase price due to the Buyer’s tax benefits, maintains transaction efficiency of stock sale, avoids the complications of an asset-by-asset transfer, and might receive more favorable overall tax treatment compared to straight asset sale. The election process involves specific timing and procedural requirements, however. The election must be filed by the 15th day of the 9th month following the acquisition month, requires formal agreement between Buyer and Seller, and is irrevocable once made. In addition, the purchase price must be allocated among assets according to IRS rules.

While potentially advantageous, a Section 338(h)(10) election may result in state tax treatment that differs from federal treatment, and there are complex valuation and allocation requirements. The election may result in higher taxes for the Seller when compared to a straight stock sale.

Summary

The choice between an asset sale and a stock sale requires careful consideration of a number of factors, including the tax implications discussed above, as well as liability exposure, transaction complexity, and circumstances that may be applicable to the particular business involved. Asset sales generally favor Buyers due to tax benefits and for reasons of risk management, and stock sales often appeal to Sellers due to tax efficiency and transaction simplicity. The optimal structure depends on the specific circumstances of the transaction and the priorities of the parties.

The availability of Section 338(h)(10) elections adds another layer of sophistication to the structure decision, potentially offering a beneficial hybrid approach that combines the advantages of both asset and stock sales. However, this option requires careful analysis and consideration of all parties’ circumstances and objectives.

None of the information provided in this article constitutes legal advice or tax advice. Every situation is different and should be thoroughly reviewed by and discussed with your legal and tax advisors. Please do not rely on the contents of this article as the basis for making decisions regarding your particular situation. If you are contemplating the purchase or sale of a business in the State of Maryland, Lewicky, O’Connor, Hunt & Meiser stands ready to provide legal support for your contemplated transaction.